A possible future for expanding cognition: Ted Chiang shares thoughts on being a cyborg

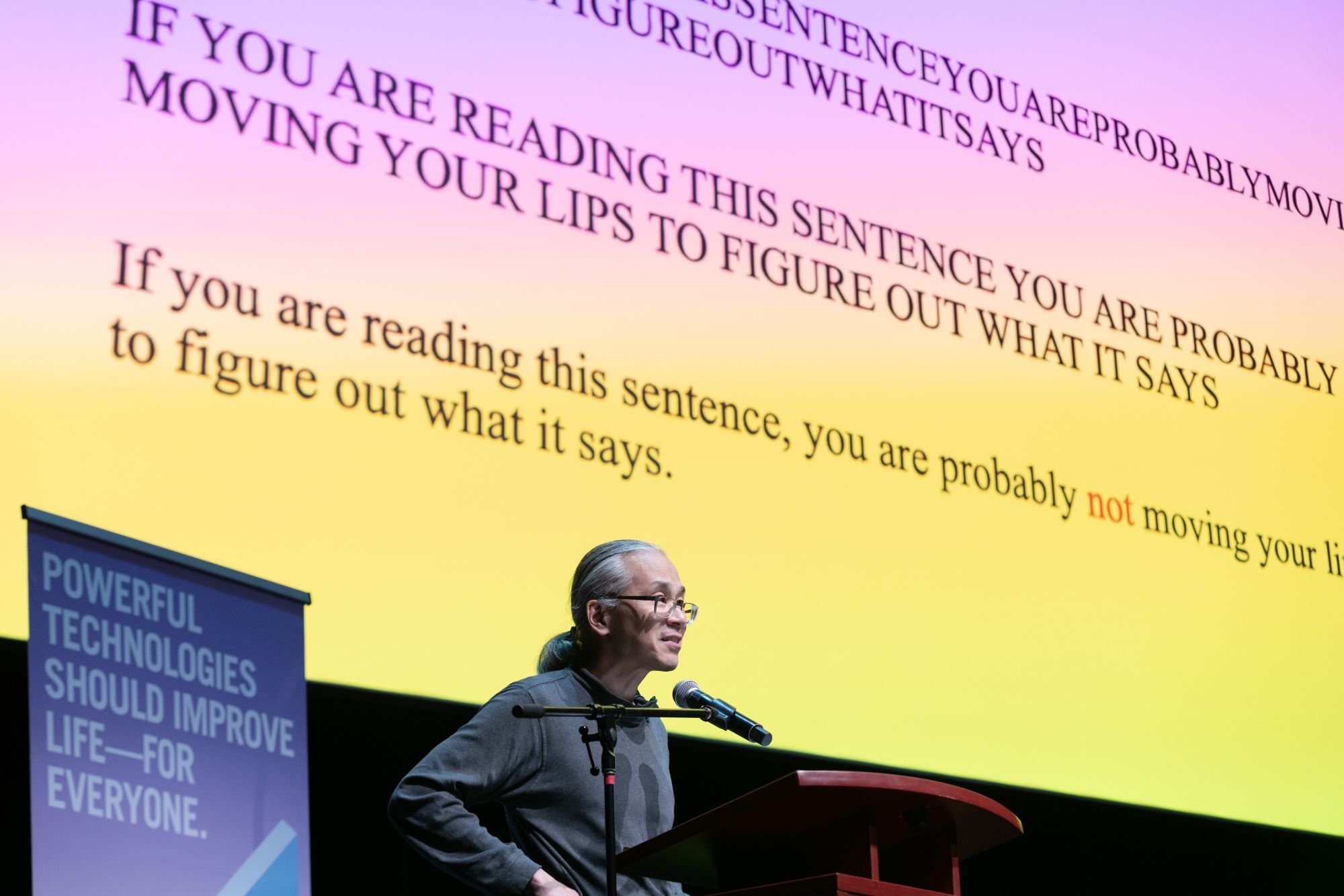

Internationally acclaimed science fiction writer Ted Chiang lectured to a sold-out crowd at the Isabel Bader Theatre on March 15, 2024. All photos by Johnny Guatto.

What is the relationship between technology and human cognition? How have writing and language been deployed as technologies throughout human history? And what does the future of computers hold—will it give rise to a new kind of cognitive technology?

A sold-out crowd gathered to hear acclaimed science fiction author Ted Chiang reflect on these and related questions last week at an event co-hosted by the Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society (SRI) and the Department of English at the University of Toronto.

Photos from Ted Chiang’s lecture “Thoughts on being a cyborg” at Isabel Bader Theatre.

Hosted by Avery Slater, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto's Department of English and faculty fellow at SRI, the event saw Chiang lecture on the ways in which we imagine—or perhaps cannot begin to imagine—the technologies of the future. His lecture then delved into everything from the transcription of speech into writing to the differences between oral cultures and cultures of literacy, and the idea that computer programming languages are “tools for thinking.”

Chiang’s lecture was followed by an on-stage conversation with Slater, an expert in 20th and 21st century literature whose research incorporates the history of AI, science and technology studies, human and non-human languages, and emerging issues in the automation of creativity. After the discussion, Chiang answered questions from the audience.

“As a thinker and writer, Ted gets right to the heart of the matter,” said Slater as she welcomed Chiang to the stage, calling him “one of the most brilliant minds of our time.”

“In each our own ways, we find ourselves struggling to catch up on vital questions,” said Slater. “How does technology affect our cognition? What does it mean to see ourselves as cyborgs? Have we been cyborgs for a long time now, unawares?”

“Ted’s writing breaks the time barrier,” said Slater, “taking us not into the future so much as those thinnest, most meaningful and fragile dimensions of the story of our collective lives.”

Chiang began by talking about representations of particular kinds of technologies in the sci-fi novels Imperial Earth (Arthur C. Clarke, 1975) and Snow Crash (Neal Stephenson, 1992), posing the question of what these novels say about “our ability to imagine our interactions in the future.”

Certain advancements in real-life technologies were enough to “radically expand our conception of what was possible,” said Chiang, between the publication of Clarke’s book and Stephenson’s almost 20 years later.

So, are we now—at this particular moment in history—capable of imagining “the next paradigm for interaction?” Chiang asked.

Chiang proposed we think about writing as a technological invention; “it was not learned spontaneously,” he pointed out. And developments in writing—such as the introduction of spacing between words and upper/lower case letters—“rendered the underlying structure of language visible.”

“It’s hard to imagine what I’d do or be good at in an oral culture,” joked the writer. “I’m not a performer, so it’s hard to imagine what my thought processes would have been in that setting.”

Having won multiple Hugo Awards—the most prestigious prize in literary science fiction—as well as countless other accolades throughout his career, it’s unsurprising that the author holds writing in high esteem as an indispensable tool for processing thought.

Comparing writing to other technologies that help us think, remember, and calculate—such as the smartphone—Chiang pointed out that “literacy is something which cannot easily be taken away.”

If writing is and has been such a powerful cognitive technology throughout its history, Chiang then wondered whether humanity would develop another cognitive technology that is “similar to but better than writing in the future.”

“I don’t know what it would be,” he said, “but I have to assume there will be one.”

Chiang concluded his talk by addressing the common criticism that technology is “dehumanizing.” While he noted that there are plenty of situations where technology is dehumanizing, such as “when it is used by capitalism to reduce us to cogs in a machine or to extract money from us,” the written word is one of the exceptions.

“The written word is human,” he said. “It helps us be creative.”

Ending on a profoundly optimistic note, Chiang wondered whether the future of computers will give rise to a new cognitive technology, and as a consequence “new ways to be creative, new ways to be smart, and new ways to be human.”